The homeschooled entrepreneur on a mission to change government

Robyn Scott was homeschooled in Botswana. Today, she is co-founder and CEO of Apolitical, a government learning platform used by over 250,000 public servants in 160 countries.

In Henrik Karlsson’s survey of the biographies of people who have made significant contributions to literature, mathematics, music, and philosophy, he found some recurring elements in their childhoods: 95 percent of them spent their childhood surrounded by adults who were unusual or exceptional. Two-thirds of the sample were homeschooled until the age of 12. As children, they spent time with adults who took them seriously — adults who assumed they had the capacity to understand complex topics and, therefore, invited them into serious conversations and meaningful projects. They also had large amounts of time to roam about and relied heavily on self-directed learning. When reading Robyn Scott’s memoir of her childhood, Twenty Chickens for a Saddle, you can’t help but notice the parallels - just take those elements and add in a healthy dose of adventure!

Robyn’s family moved to Botswana after her parents made an overnight decision to relocate from New Zealand:

“I’ve had enough, Lin,” he said. “I’m stopping medicine. And I want to move to Botswana.” Mum, who loved impractical, overnight, career-changing, continent-shifting decisions as much as Dad, said, “When do you want to leave?”.

Robyn’s father was a reluctant doctor looking to escape the profession but he hoped working in Botswana could help him fall back in love with his career. He worked as a flying bush doctor, travelling by plane to remote clinics across the country. He was taught to fly by his father, Grandpa Ivor, who lived nearby. Ivor was a commercial pilot in Botswana having learnt to fly during the second world war. He was constantly working on new, largely unsuccessful, business ideas.

‘Grandpa might tell hours of stories about the old days, or—if I wanted to talk—provide an audience willing to listen, seriously and without teasing, to anything I said.’

Robyn’s father treated many patients suffering from HIV and battled to make the government take decisive action as he watched the AIDs pandemic reduce life expectancy in Botswana from the mid-sixties—one of the highest in Africa at the time—to the mid-thirties. He was fascinated by alternative therapies such as acupuncture and homoeopathy and he developed interests in biodynamic farming ‘forming the Biological Producers Association, the first in New Zealand to certify organic food, and taking a prominent role in the debate about the impacts of chemical pesticides on health’.

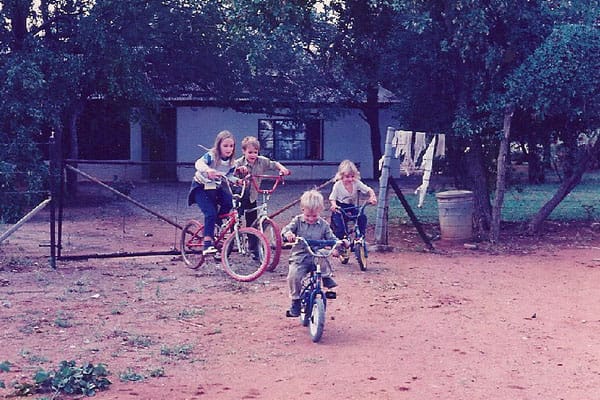

Robyn, along with her two siblings, Damien and Lulu, was homeschooled by their mother, who believed in giving her children an education centred on play and curiosity.

Her mother discovered her enthusiasm for curriculum-free education after an epiphany during her last year of university.

"That was the year that she had met David Jenkins, a pioneering researcher into the health benefits of dietary fibre. Eyes sparkling, Mum would tell us how she’d been swept along by his passion for his work; how, for the first time, grades became secondary to knowledge. “He revolutionised my outlook on health, and on education,” she would sigh dramatically. “I only realised then that I’d spent most of my education half asleep—learning how to pass exams well, and very little else.” Sparked in university, Mum’s fascination with the role of nutrition in health and disease never waned. Nor did she ever forget her awe at the pleasure of becoming really interested in something. “And that transformative year lives on still”—Mum would smile—“in my whole-wheat bread and homeschooling.”

They did not have formal lessons, instead her mother focussed on encouraging her children to do anything that involved learning.

For the most part that involved playing and listening to their mother read them books, sometimes for whole days. She introduced them to the likes of Ursula K. Le Guin, Peter Dickenson, Lucy Boston and JRR Tolkein.

‘Books with vast, rich stories that swallowed you into their worlds. Books that left you, when the last page had been turned and the dust, flies, and mind-numbing heat resurfaced in your consciousness, pining for the characters like left-behind friends.’

Robyn’s parents accepted their children would be exposed to risk, they often used mishaps to encourage courage and persistence. Her father bought Robyn an unbroken pony for her to learn to ride on. She spent as much time picking herself up off the floor and picking out thorns as she did riding. Damien, who was fascinated by mechanical objects and particularly explosives, had a near miss after exploring an old mining dump near their house. Playing with fuses he set off an explosion, barely avoiding serious injury.

When Robyn and Damien did eventually try school for the first time they were shocked by one thing, boredom. In a decade of homeschooling they’d never experienced boredom and only when they joined a school did they realise how lucky they’d been.

After completing her education Robyn set up an organisation teaching prisoners to code. At the time it was only the second such organisation in the world. But it didn’t take her long to realise how downstream she was of all the systemic problems that were leading people to find themselves in prison. Within just a couple of weeks of working with prisoners in South Africa she saw that ‘99% of those people are there not because they're psychopaths but because they have been let down at some point in their life by education policy, by social policy, by health policy and it felt that we would be stemming these bleeding wounds rather than stopping them being inflicted.’ Robyn knew that in her next venture she wanted to work at a systems level, upstream of the many problems facing society.

During Robyn’s childhood she lived in various countries: New Zealand, Botswana and South Africa. She would see something work well in one country and think to herself ‘why can’t my government do that?’ Robyn and Apolitical co-founder Lisa Witter thought there should be a community where public servants from different countries could discuss shared challenges and learn about potential solutions.

The scale that governments operate at was a key motivation, Robyn writes:

‘Around 200 million people work in the public sector globally. In many countries, government is the largest employer and the people government employs make some of the most consequential decisions of any professionals: legislation that affects every citizen and every industry, spending that accounts for 40 cents in every dollar, or $30 trillion dollars a year.’

These 200 million people working for governments weren’t being served well by existing learning and development opportunities, ‘Private sector professionals have come to expect ongoing learning that enables them to keep pace with rapidly evolving jobs, public servants still expect siloed institutions, 1990s tech solutions, and dismal upskilling opportunities. Only 5% of public servants say the internal learning resources offered to them are ‘very helpful’’.’

After founding and running previous businesses, Robyn knew that carefully aligning Apolitical’s business model with its social impact was essential to ensure they were constantly incentivised to focus on their social impact. By creating a product with the purpose of making governments more effective, she believed their profit-motive should be perfectly aligned with having a positive impact. Sadly, as anyone who has read horror stories about government procurement will know, a mission of serving the government is not enough to ensure good behaviour. So Robyn implemented a series of constraints to make sure Apolitical remains true to its mission. Apolitical is a B-Corporation, which commits them to ‘globally recognized standards of responsibility and accountability, and to a societal, environmental, and governance bottom line as well as a financial bottom line.’ Apolitical only sought out investors who were aligned with their mission and had clear values. They actively turned down investors they didn’t see as a good fit. Finally, Apolitical consults its own users, some of whom act as advisors, on how they monetise and use data.

Today, Apolitical is used by 250,000 public servants in around 160 countries. Robyn is working at a systems level with enough leverage to have a huge impact. Despite being only a 55-person company, Apolitical has created courses for public servants with partners including the University of Oxford, the London School of Economics, Georgetown, and Stanford Online. In 2024, they received a $5 million grant from Google.org to train a million public servants around the world on how to use AI. From climate to health and education, Apolitical is working on critical areas for governments around the world. It will probably take at least a decade to see or understand Apolitical’s true impact, but the opportunity is enormous. If they can ensure that 1% of global governments’ $30 trillion annual budget is spent 50% more effectively, they could unlock $150 billion each year for society. It will be exciting to see their progress from here.

Comments ()